Food for Thought

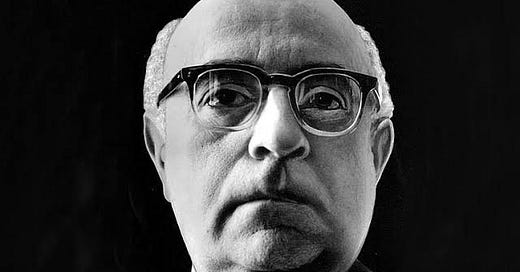

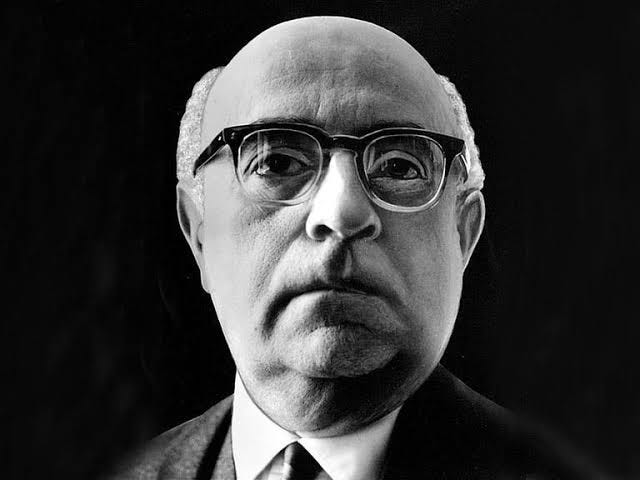

In 1959, Theodor W. Adorno, a German philosopher who was forced into exile in the US during WWII, held a speech about the American and German understanding and practice of culture. The differentiation between these two cultural understandings is relevant today and can help observe and analyze current socio-economic topics. Despite some of the fine details being lost to the later transcribed format, making Adorno hesitant to it’s publication, it presents some interesting points.

Adorno describes culture to be the interaction between humans and nature. This specific definition of culture has evolved and is no longer current, but is nevertheless interesting to explore. According to his findings, both Americans and Germans stick to this definition, although their cultures manifest in significantly different ways. One of them attempts to tame nature, be it within the human self or the human’s surroundings, the other tries to preserve nature. This could mean seeing an inherent sense within it or finding it valuable enough to explore and maintain.

Those who have grown up in Germany or Europe may be able to attribute these two interpretations to their corresponding country, at least when in direct comparison. While the first is supposedly an “American way of thinking”, the latter is considered more German. It is possible that the German cultural understanding functions as a veil, hiding socioeconomic inequalities in Germany.

We seem to seek shelter in the philosophical achievements of the past to compare ourselves to countries, who are presumably, at least in a moral capacity, doing worse. As if the fact that capitalism and the “taming” of our nature are in some ways contradictory to common ideals within German philosophy (especially Hegel), made our legitimate practice of it justifiable–or at least more justifiable than “what the US is doing”.

Capitalism is a loaded word; one must not try to attribute any different moral capacity to it than what is found within this philosophy to begin with. This idea is not only patronizing but an easy way to escape responsibility. In academic spaces, we especially tend to recognize injustice without stepping into action against it, for this very reason. This is a common critique of German idealism and the attempt to make German society civil as a whole.

Although this is at best a misinterpretation of the actual philosophical movement (if not outright false), its cultural influence has given more leeway to inward thinking that contributes less to an overall change in societal structure. In this way, culturally speaking, Germans may like to comment on immorality and expect change from others, assuming that self-reflection from our idiotic counterparts could solve our problems.

Most of us feel we are fighting an upward battle that can never be won unless everyone else comes to their senses. That means convincing anyone and everyone that there is a “rational” solution they just haven’t understood yet.

On the other hand, the American ideal suggests the possibility of finding happiness within the capitalist society by working hard to earn the money deserved. There is no need to explain why there are many cases in which people work very hard and ambitiously and have been failed by this very dream.

This is one of the reasons Americans may be more easily subjected to social injustice in legislation, because it can be conveyed in a way that seems to secure the idea of “American” freedom, which its citizens are dependent on. Social policies seem to many people as a hindrance to their achievement of the “American Dream”, which by definition includes being fully responsible for one's achieving it and leaves little room for equity.

But the dream goes further—it’s not just wanting to achieve this dream yourself, but living in a country where everyone can achieve it from their own resources. This, as we know, is simply not the case.

Isn’t this overlooking the fact that German politics are usually a lot more intrusive to its citizens than US politics because of social policies and the attempt at equality?

Three aspects show that this does not necessarily contradict the previous observation:

Firstly, trying to fight economic injustices through social politics is forgetting that we do currently live in a reality that requires a lot of material as well as intangible wealth. This isn’t entirely compensated by the state because it is often underestimated.

In that sense, one could argue that many of these policies aren’t exactly “social”. Finding happiness is being made actively dependent on monetary recognition, which is why people are asking for more. Looking down on disparity and deciding that “wanting out” is too much to ask for, is completely disregarding the privilege that comes with finding a contented life outside of these constraints.

It is ignoring the fact that this type of dependency on wealth is not a decision the individual makes, but is primarily forced onto every one of us by a system. The fact that repressive policies are often supported by those affected by them is not proof that the policies are beneficial. Within the existing systems, they are presented as the only option when they often aren’t.

Secondly, a type of ideology around American culture gives the state a lot more power over its people compared to the German state, without having to enforce laws directly upon its citizens. You may argue that due to the US being a country of immigrants, there is no homogenous culture, but there is an overall idea of what America means. American culture relies less on physically observable traits of culture, and rather upon metaphorical (and often mythical) premises that all Americans rely on when building national identity.

The US government holds an exceptionally large responsibility in representing its citizens. Interestingly enough, that goes hand in hand with the population’s ongoing distrust. This distrust in the Government and simultaneous expectation leads people to hold on to a traditional set of policies while keeping the state as slim as possible on top of that foundation. Its citizens not only expect their values to be represented by the state for the sake of foreign policy, but also for the maintenance of patriotism. This makes it possible for the US government to hang on to an almost unconditional hope of its people, despite that its citizens are very critical of the state.

In contrast, German politics has evolved with a greater distance from the people. Whilst we are aware of the complexities of the system, we often still believe to have found a truth within ourselves that others just haven’t yet recognized. These complexities, for one, make it easier to lie back because anything that changes doesn’t change very fast, and secondly, impair our will to step into action—even on a local level, all we can do is “kleine Brötchen backen”.

In addition, expectations of what German society should look like are very different among Germans. For some, the real hope lies in shaping a functioning society that does not rely on patriotism. Despite an abundance of laws, the German government will just never be as close to the German people as the US government is to its citizens.

Within academics (of which both countries pride themselves upon), recognizing that our perceptions as individuals are different is key. This is usually not due to intelligence or any other kind of traits attributed to superiority. Many academics seem to think that there is an intellectual surplus allowing them to see past the rim of the problem.

However, being an academic also means you are trapped inside a bubble of privilege, with severance from the broader majority of society. They are not analysing the human experience from a realm outside space and time, but are humans who have naturally lost touch with other social groups. We probably shouldn’t treat our intellectual idols as such, nor think of ourselves in that way.

Furthermore, there is a societal hierarchy leaning on the assumption that anything you have earned, you have earned just as much and in the same way as anybody else. Stating the widely varying gaps between every journey does not play down anyone’s achievements but calls attention to the communal aspect of human life. We require assistance–accepting and recognizing the assistance we require is important to creating a more equal playing field within society.

These points concern both the US and Germany, regardless of cultural variation or severity.

Adorno’s description of the manifestations of culture in Germany and America isn’t fully exhausted, especially today. This still does not take away from our persistent unconscious belief that there is something ultimate about our heritage.

Of course, one develops from experience, and that has its right to consideration, but it is still essential that we think about why things happen in the countries they happen in. The socioeconomic systems we witness are not an underlying nature within people, they are an underlying system. If one assumes Adorno’s argumentative strategy, one can conclude that these systems are inherently unnatural.