Food for Thought

‘The female mind is capable of understanding analytic geometry... The difficulty may just be that we have never yet discovered a way to communicate with the female mind. If it is done in the right way, you may be able to get something out of it.’ This is a quote from Richard Feynman, a man almost mythologised in popular science culture, a truly great physicist and quite unfortunately, a huge sexist. This quote is made even worse by the fact that it was blurted out during a public lecture and that you can find a surplus of similar statements in his memoirs ‘Surely, you’re joking Mr. Feynman’, a book that is universal beloved in the pop science community, especially amongst teenagers and young adults.

Imagine being a young teenage girl interested in physics you are recommended this book by a teacher hoping to inspire you and then you come across a whole section in the book where Feynman refers to a woman he met as a ‘whore’ simply because she wouldn’t sleep with him! That would naturally leave a sour taste in your mouth and might even make you think, “These physicists seem really weird, maybe I should just try something else.” This is not a hit piece on an undoubtedly great physicist who died over three decades ago. Nonetheless, we are obligated to highlight the sexist attitude he and many like him possess and how it has been a tough, uphill battle for women to try to break into science.

Growing up as a boy, my interest in science was connected to an almost emancipatory feeling. Science was liberation, it was creativity, it was a place of freedom, where if you worked hard and had something meaningful to contribute you were the same as everyone else, I was aware of the idea of academic hierarchies, but it did seem like everyone, no matter who you were, would be treated with respect and dignity if you were a good and dedicated scientist. Of course, popular media flooded me with role models to look up to—Einstein, Faraday, Maxwell, Darwin, Feynman (yes even him), as well as great scientists from my own country like C.V. Raman and Bose and many others—and I was better for it.

Looking back, I can’t help but think that my pool of idols would’ve been much drier if I were a young girl interested in science. Chances are you if you don’t work in science, you could count the number of female scientists you know on one hand with fingers to spare. This is not because there haven’t been any great female scientists, but their numbers are significantly lower than their male counterparts. Women are objectively just as good at science as men, yet we see this disparity. I believe there are two reasons for this. Firstly, because of the misogyny ingrained in scientific culture, and secondly, the portrayal of women scientists in the media.

Science is great and incredibly fulfilling; however, going through its history, one does see an unfortunate pattern of sexism. Caltech, the university for which Feynman worked for started allowing women students in its undergraduate programmes in 1970. Cambridge, arguably the most popular university in the world, only started granting degrees to women in the late 1940s, two whole decades after universal suffrage was confirmed through legislation in Britain. C.V. Raman, arguably the most well-respected and popular physicist in India, was a massive misogynist who made it nearly impossible for women to be admitted into the Indian Institute of Science during his tenure as director.

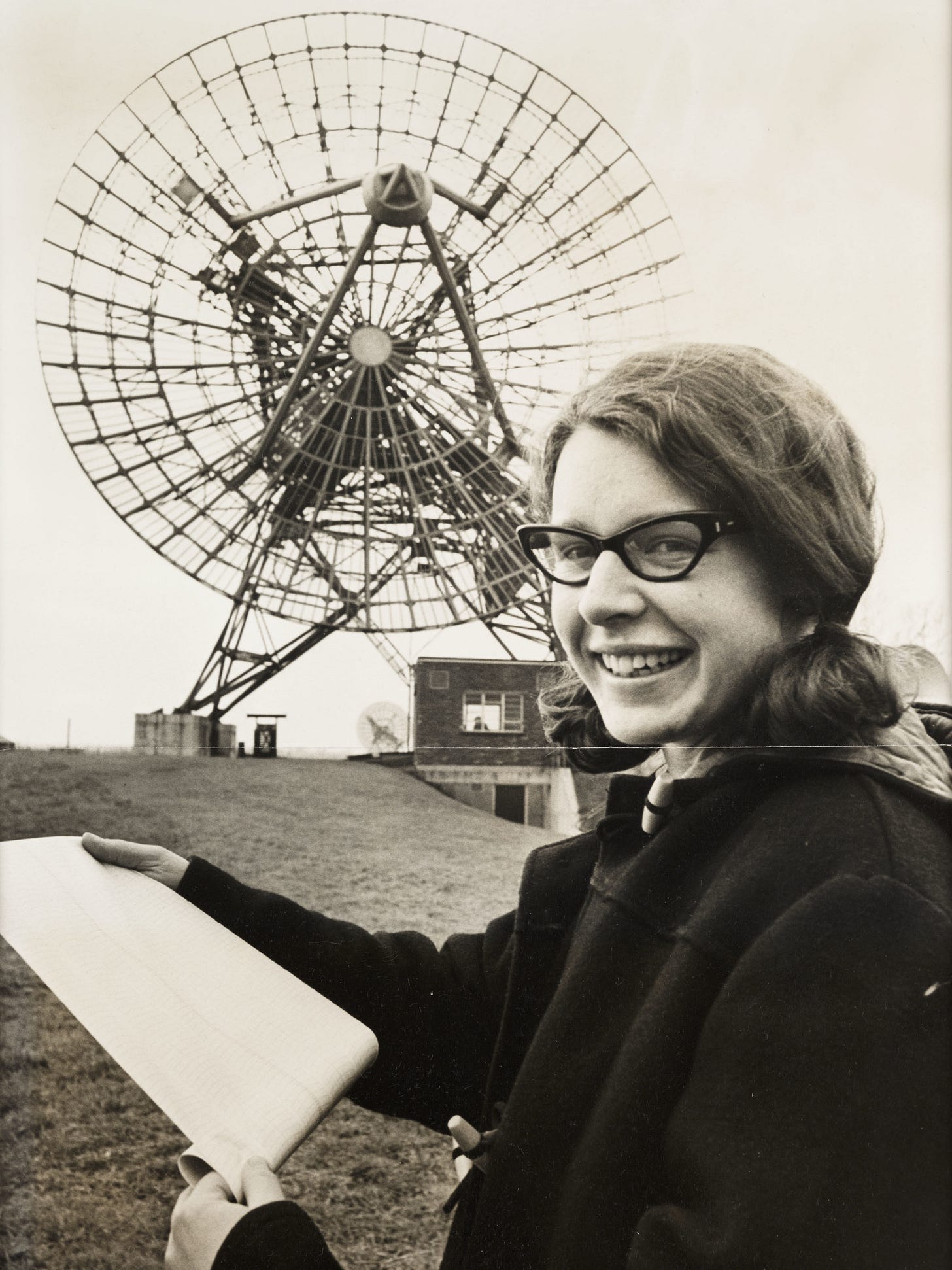

Perhaps the most obvious case of sexism in scientific culture is the story of the great Jocelyn Bell Burnell. Young Jocelyn knew she wanted to be an astronomer. In secondary school, all the girls, including Jocelyn, were sent to the cookery room while the boys were sent to the science laboratory. It was only after her parents’ protest that she was allowed to participate in the science class. She obtained her undergraduate degree from the University of Glasgow, where she recalled that it was tradition that all the guys in the room whistle and catcall and bang their desks when a woman entered the classroom.

Despite all that nastiness, she did very well in her degree and managed to secure a spot at Cambridge for a doctoral degree under renowned astronomer Tony Hewish. As a doctoral student, she discovered a stellar phenomenon called a Pulsar. Pulsars are rotating, immensely energetic stellar objects millions upon millions of light years away from us, which radiate extremely energetic electromagnetic radiation in certain intervals of time. This radiation loses its energy travelling so many light years and only reaches us in the form of weak, faint radio waves. Jocelyn not only built the radio telescope from scratch, she observed the first pulsar signals and had to convince her supervisor that these signals were representative of a legitimately new stellar phenomenon and not a result of her ‘messing up the experiment’.

The 1974 Nobel Prize for Physics was given to two people for the discovery of Pulsars, spoiler alert: neither of those two people named were Jocelyn Bell Burnel; the prize was shared by her supervisor Tony Hewish and Sir Martin Ryle, who she walked in on one day discussing the pulsar discovery with Tony Hewish- a discussion she laments “I should’ve been a part of in hindsight”.

Even when the press caught wind of the news, her supervisor was flooded by questions regarding the physics of the discovery and how significant it was for the field of astronomy, while Jocelyn was primarily inquired over the ‘human’ aspect of the story, with reporters even going as far as asking her how many boyfriends she had and if she would identify herself as a blonde or a brunette. Hewish didn’t do much to help her and dishonourably referred to her as a mere ‘student’ when giving talks on the new discovery. Today, Jocelyn Bell Burnell is a successful and world-renowned astronomer, but she never won the Nobel Prize for her discovery and had to watch helplessly as her contribution was essentially diluted by media outlets.

This brings us to the second part of our problem—the portrayal of women in science in the popular media. My own interest in science originated from a pop science book as a child called ‘Brahmand Sankshipti’ or ‘The Universe in Brief’. The book was written by a criminally underrated Indian science writer,, Gunakar Mulley and introduced me to the world of planets and stars, of Galileo and Kepler, of discovery and curiosity. I am many of the individuals who owe their interest in science to some form of popular media, be that movies or books, or TV series.

How we portray a certain subject, including the people behind that certain subject, carries a great degree of influence. Studies have shown time and again that the influence of female role models has been essential in shaping the careers of many great women scientists. Even as a kid interested in science, the only woman scientist I was exposed to before turning 15 was Madam Curie, whom I was introduced to thanks to my high school physics class.

Women scientists portrayed in popular media are either shown to be ruthless career women with a massive chip on their shoulders whose hearts are ultimately softened by a male romantic interest (the similar perpetual portrayal of Madam Curie in dramatized films is quite shocking) or are fetishized to fit the male gaze- the nerdy girl with glasses who knows her way around a computer and is hiding a supermodel body under her oversized jumper.

Without all the sex and romance, their portrayal is in the periphery to the men in their lives. After all, people know less about Ada Lovelace’s contributions to computation and more about her romantic affair with Voltaire and her tumultuous relationship with her father Lord Byron.

One might say, ‘This is old news, surely things have changed in the 21st century!’ There is, of course, truth to that as well. If a professor made a statement adjacent to Feynman’s quote at the beginning of a lecture, they would find themselves in a lot of trouble in any half-decent university. The percentage of women in STEM fields has increased a great deal since the latter half of the 20th century; almost half of the total STEM graduates in 2021/22 worldwide were women. Most universities have strict policies to prevent instances of sexism and misogyny in academia and to promote the participation of women in STEM fields.

For example, India has a certain number of positions within government-run institutes of higher education reserved for female candidates. Even films have recently seen a change in the portrayal of women scientists; films such as The Martian (2015), Proxima (2021), and Gravity (2013) all challenged the archetype of women scientists in mainstream cinema and popular media. However, the fight is long from over.

In June 2015, the University of California, Berkeley found legendary exoplanet researcher Geoffrey Marcey guilty of having violated the university’s sexual harassment policy between 2001 and 2010. Not only had Marcy’s horrible behaviour, which consisted of groping female students and an all-too-long list of inappropriate actions, led to many women leaving physics altogether, it had caused irreparable damage to the psyche of the victims and the reputation of both the field and the institute. What made matters worse was how many people already knew Marcey’s abhorrent behaviour and still, more often than not, stayed passive; complaints regarding Marcey fell on deaf ears. Geoffrey Marcey left the faculty of Berkeley not too long ago, and the damage persists. Even though we see high graduation rates amongst women in STEM, the proportion of women working in STEM jobs is still a meagre 26-28 % worldwide. S

cience is a collaborative field and is naturally emancipatory; that is, science by itself, independent of social constructs, does not care about your sex, religion, or where you come from, as long as you work hard and have something meaningful to say, you are respected. We must still acknowledge that there are there is still a lot to fix to deconstruct sexist and misogynistic notions which persistently present within the scientific community. If we don’t try hard to do away with them, we not only do a disservice to science but also to the many women who have worked so hard and so long to make their place here.